from:China Three Gorges Corporationdate:2020-10-20

“Chinese sturgeons, safe journeys!”“You’ve eaten well but now you’re on your own.”“Keep going all the way to the sea, regardless of wind or rain!”

So went real-time online comments displayed during the livestream of an April 22 event in Yichang, central China’s Hubei Province, where 10,000 Chinese sturgeons (Acipenser sinensis), an endemic and critically endangered species, were released into the Yangtze River. When the sluice gate of the transparent water tank opened, the sturgeons were released from the environment in which they had been bred. Via a water slide, they entered the Yangtze River. This was the 62nd release by the Chinese Sturgeon Research Institute (CSRI) of the China Three Gorges Corporation.

“The event normally draws many spectators from among volunteers and residents along the river,” said Dr. Jiang Wei, director of the CSRI’s Hydrobiology Laboratory, “But because of the outbreak of COVID-19, this year’s event had no crowds. Instead, it was all online. The release still added to the stock of Chinese sturgeons in the natural environment all the same.” Jiang has participated in this event for 10 consecutive years. He began studying conservation and monitoring of rare species of fish in the Yangtze River while still a doctoral student. As a researcher at the CSRI, he has mostly concentrated on monitoring and researching the natural population of the Chinese sturgeon.

For dozens of years, the CSRI has intensified its efforts to achieve scientific and technological breakthroughs in the conservation and breeding of endangered rare species of fish in the Yangtze River, including the Chinese sturgeon. Conservation efforts for the Chinese sturgeon were enacted by the government and relevant institutions in the 1980s. In 1984, the first generation of artificially-bred sturgeons was released. Since then, the annual event has continued to draw participation of people from all walks of life.

Yangtze River Strains

The Yangtze River is considered the mother river of the Chinese nation. It originates from the Tanggula Mountains in western China’s Qinghai Province and flows through 11 provinces and municipalities before reaching the East China Sea. It ranks near the top of rivers globally in terms of aquatic life. The Yangtze hosts more than 4,300 species of aquatic life including 430 species of fish, 170 of which are unique to it.

The Chinese sturgeon is one of the oldest vertebrates on earth with important ecological and scientific research value. Its origin can be traced back 140 million years to the age of dinosaurs. It’s one of the largest, longest-living and most sophisticated species of fish in the Yangtze River. After hatching in the upper reaches of the river, juveniles swim downstream into the sea to mature. They stay for more than 10 years to mature sexually before finally swimming upstream back to their breeding ground to spawn the next generation. They then return to the sea again. Since the 1980s, environmental changes, overfishing, water pollution, and other adverse factors have caused a steep decline in the natural population of the Chinese sturgeon. In 1988, it was listed as a first-class national protected animal by the Chinese government.

Of the 27 species of sturgeons worldwide, 23 are endangered, and 17 are listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) as critically endangered. In 2009, the Chinese sturgeon was listed by the IUCN as“extremely endangered.”In 2007, the white dolphin (Lipotes vexillifer), a Yangtze River freshwater cetacea known as the“aquatic panda,” was declared functionally extinct. Dr. Du Hejun, another researcher at CSRI, previously worked at the Institute of Hydrobiology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, where he witnessed Qi Qi, the last male white dolphin, fail to find a mating partner, which led to the functional extinction of its species. In 2019, the Yangtze River paddlefish (Psephurus gladius), a ferocious fish known as the“king of freshwater fish in China,” was also declared extinct.

The functional extinction of Lipotes vexillifer and Psephurus gladius were stirring milestones for the Yangtze River.

In addition to the Chinese sturgeon, surviving flagship species in the Yangtze River ecosystem include Dabry’s sturgeon (Acipenser dabryanus Dumeril), Yangtze finless porpoise (Neophocaena asiaeorientalis), and others. Are they too destined for extinction?

“The causes of extinction can be quite complicated,” commented Jiang. “There’s nothing we can do for those that are gone. All we can do is try our best to preserve surviving endangered species.”

“Since the 1980s, our predecessors have been doing a lot to save the Chinese sturgeon,” Jiang continued. “While developing four world-class hydroelectric stations on the Yangtze River, the Three Gorges Corporation carried out a series of activities related to conservation of rare species of fish including scientific research, artificial breeding, and adding to the wild population. Since 1984, the CSRI has released more than 5.03 million Chinese sturgeons and 28,000 second filial generation Chinese sturgeons into the Yangtze River. Life in the natural environment will be difficult for released sturgeons. They must swim long distances and search for food on their own while avoiding hazards like fishing nets and propellers. And it takes a long time for them to sexually mature. That’s why so few have returned to Gezhouba Dam to breed. During the months of upstream migration, they do not eat. So, they have to be physically prepared for the arduous task. Individuals with good health, excellent germplasm, and diverse genes are more likely to survive. Smaller individuals are more likely to face pressure in the wild and have meager prospects reaching maturity.”

Homecoming

In the 1980s, when the Gezhouba Dam was built on the Yangtze River, migrating Chinese sturgeons gathered near the dam to form a new spawning ground. The spawning period of the Chinese sturgeon in the wild is from October to November every year.

November 24, 2016 was a big day for Jiang. That morning, he and his colleagues were searching for sturgeon eggs on the river when they noticed some charcoal gray particles in a net about 400 meters from the dam.

“Those are sturgeon eggs!” Jiang exclaimed. “We found them at last!” They took some back to their laboratory for incubation. Over the following week, they succeeded in collecting more eggs.

“Some experts thought the eggs might contain hybrid sturgeons,” said Jiang. “But our studies confirmed they were genuine wild Chinese sturgeon eggs. That meant that the wild Chinese sturgeon population was surviving tenaciously.

“The wild Chinese sturgeon eggs were hatched with artificial insemination and spawned a first and second filial generation of Chinese generations are first-class nationally protected animals in China.” In 2009, his institute succeeded in artificially breeding the first individual of the second filial generation Chinese sturgeon. Since then, they have succeeded in more attempts at building an artificial Chinese sturgeon breeding system.

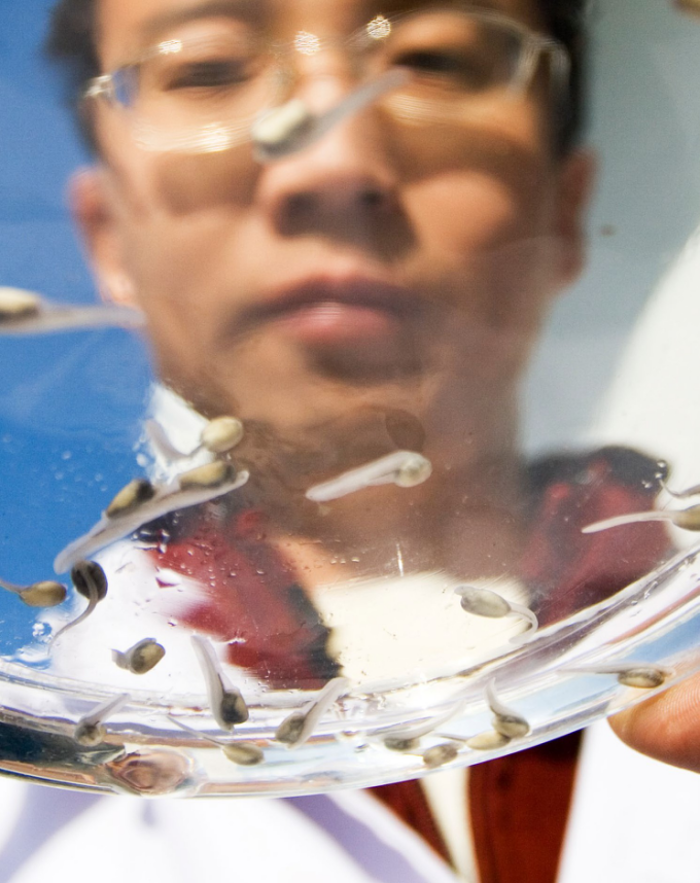

The release of artificially-bred sturgeons will undoubtedly add to the sturgeon population in the wild. A month before a release, the CSRI selects healthy and well-fed juveniles and cultures them in a simulated natural environment with flowing natural water and food to familiarize them with the big river. During this period, sampling inspections such as germplasm identification, fish quarantine, and biological physical examination are carried out for files.

According to Jiang, the group of Chinese sturgeons released this year was the largest yet. It was also the most diverse, with a combination of fry, fingerlings, and adults born from 2009 to 2019, including 10 males born in 2009. This diversity can add to the various age groups of sturgeons in the wild. The male individuals are expected to adjust the gender imbalance among sturgeons in the natural environment.

Tracking for Conservation

It’s impossible to locate the released fish in water with satellite positioning, so how are they tracked?

At present, four methods are used to track released sturgeons: PIT tagging, sonar tagging, T-shape tagging, and DNA tagging. With all of them in concert, released fish can be tracked throughout the entire river. When a tag is within the range of a scanner, it can identify the individual. So far, an 1,800- km long tracking system has been built to cover the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. It is the most far- reaching and comprehensive system of its kind in China now.

The tracking at such large scale began in 2014. Tracking data from 2019 individual. So far, an 1,800- km long tracking system has been built to cover the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. It is the most far- reaching and comprehensive system of its kind in China now. The tracking at such large scale began in 2014. Tracking data from 2019 showed that 73.3 percent of released individuals had survived the length of the river and reached the sea.

“Sturgeons’ migration is a fairly long process,” explained Jiang. “Some individuals swim all the way downstream to the sea, while others may swim sideways into tributary lakes such as Dongting and Poyang before they return to the main stream. The tracking of those released this year is ongoing.”

Jiang and his team attached tags to the released sturgeons to track them long-term. The main purpose of the tracking is to identify wild stock from artificially-bred stocks for evaluation of the releases.

Jiang thinks the long life cycle of the Chinese sturgeon is one of the problems with conservation because it takes more than 12 years for the fish to become mature enough to breed in the upper reaches of the river. It’s impossible for the species to rebuild its population as quickly as more common species can. As a species at the upper end of the biological chain, it faces greater difficulty recovering in the declining water environment with fewer aquatic organisms. Since 2011, the Three Gorges Project has carried out experiments in biodiversity conservation for nine straight years. For example, they built artificial flood peaks to create better conditions for breeding of bluefish, grass carp, silver carp, and bighead carp, the four major species in the Yangtze River.

“Stock of the river’s four major species has declined more than 90 percent since the 1950s,” said Jiang. “But the population is finally recovering thanks to conservation efforts and fishing bans. Since January 1, 2020, fishing in the 332 nature reserves and aquatic germplasm conservation areas in the Yangtze River Basin has been completely banned. Starting January 1, 2021, fishing in the Yangtze River main stream and major tributaries will be suspended for 10 years.

“More importantly, since implementation of policy to protect and build the ecological environment of the river, the conditions have continuously improved.”

In recent years, President Xi Jinping inspected the Yangtze River Economic Belt several times and called for all- out efforts to protect the waterway. “We must not allow the ecological environment of the Yangtze River to continue deteriorating in the hands of our generation, and we must leave our descendants a clean and beautiful Yangtze River,” said the President at a seminar on promoting the development of the Yangtze River Economic Belt in Wuhan, Hubei Province, in 2018.

It has also been encouraging that residents along the river have gradually improved awareness of Chinese sturgeon conservation. Jiang noted that when they first started installing tag signal scanners on fishing boats and wharves, many people did not have any idea about the species or the importance of its conservation. Some people didn’t want their equipment installed. Nowadays, however, improved awareness has motivated residents to enthusiastically cooperate with the efforts.

“Everyone can help protect the ecological diversity of the Yangtze River just by doing things like disposing of trash properly, stopping fishing, and avoiding discharging sewage into the river,” said Jiang.

After they complete tracking the sturgeons released this year, Jiang and his team intend to analyze released sturgeons after they reach the sea to better assess the situation in the wild.

Technicians check on Chinese sturgeons at the Three Gorges Rare Fish Species Conservation Center in Yichang, Hubei Province, on August 7, 2020. (VCG)

Ten thousand second filial generation Chinese sturgeons are released into the Yangtze River in Yichang, Hubei Province, on April 22, 2020. (VISUAL.PEOPLE.CN)

Tel:+86-25-84152563

Fax:+86-25-52146294

Email:export@hbtianrui.com

Address:Head Office: No.8 Chuangye Avenue, Economic Development Zone, Tianmen City, Hubei Province, China (Zip Code: 431700) Nanjing Office: Room 201-301, Building K10,15 Wanshou Road,Nanjing Area, China (Jiangsu) Pilot Free Trade Zone,Jiangsu Province,China (Zip Code:211899)